Descargar informe completo

Download Complete Report in English

The cause of hunger is essentially political

The cause of hunger in Cuba is not economic or climatic, but essentially political. The crisis in food production is the result of the systemic national crisis of a failed regime of governance managed by an incompetent government.

The food crisis in Cuba has reached dramatic levels, revealing the structural failure of the economic and productive system. According to data from the World Food Program (WFP) and UNICEF, the country now depends on international donations to guarantee a minimum supply of basic products, while more than 80% of the food consumed is imported largely from the United States. This dependence, coupled with a lack of investment in the agricultural sector and state control over economic activities, has made food one of the main daily concerns of Cubans.

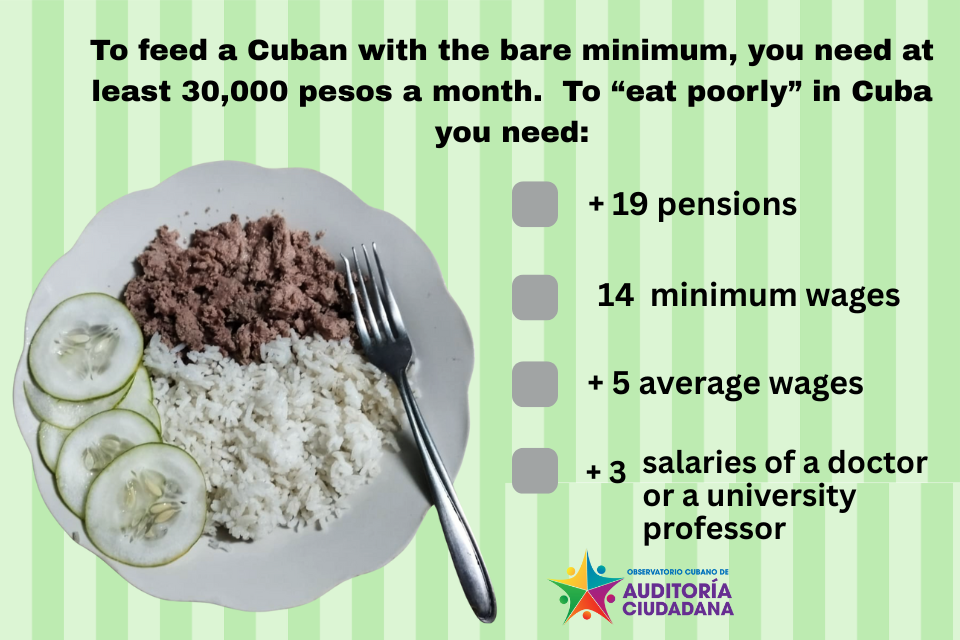

Wages, pensions, and the cost of eating

A survey conducted by OCAC in Havana in June coincides with a survey conducted in Santiago de Cuba by Bloomberg last May. To feed a Cuban with the basics, at least 30,000 pesos per month are needed. This explains why most Cubans can barely manage two meals a day and, in many cases, cannot even include protein in their diet.

Wages and pensions in Cuba are not enough to cover the cost of the basic basket of goods. According to data compiled in June by the OCAC, with a minimum wage of 2,100 CUP and a minimum pension of 1,528 CUP, a worker or retiree needs between 14 and 19 minimum wages to eat poorly for a month. It would take 5 to 3 salaries of a university professor or a doctor to eat the essentials. One Cuban Pesos equals 0.04 cents of US Dollars.

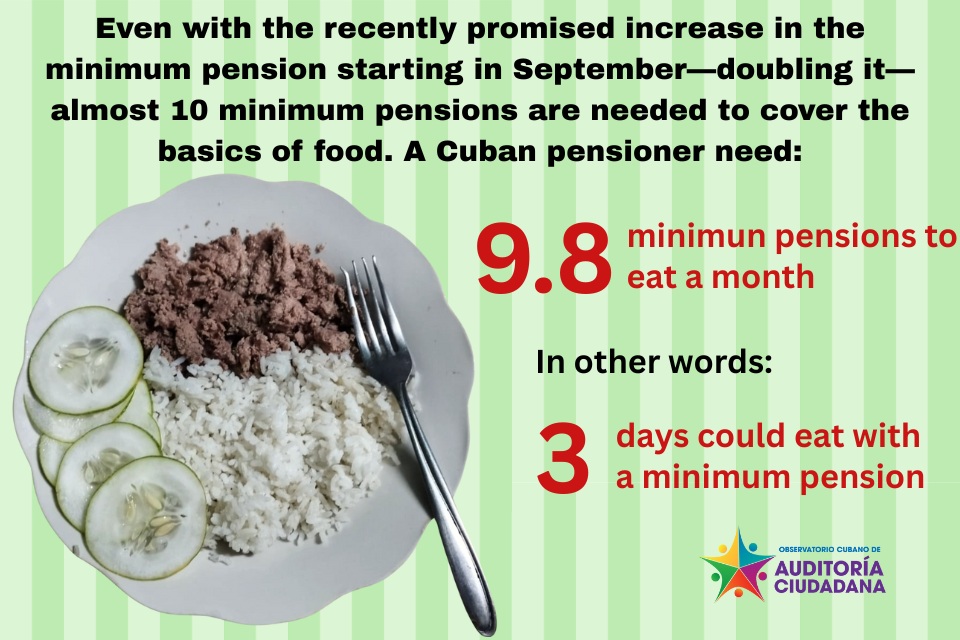

Even with the recently promised increase in the minimum pension starting in September—doubling it—almost 10 minimum pensions are needed to cover the basics of food. In other words, the populist measure announced will allow a Cuban pensioner to have enough money to eat three days a month, instead of the one and a half days they had in June, by the time of this investigation. This is without considering that accelerating inflation will reduce purchasing power.

Bloomberg’s calculation coincides with that of the families interviewed by OCAC in Havana in June. “For breakfast, bread with an omelet (made with one egg) and a glass of mango juice. For lunch, rice with chicken picadillo or ‘perritos’ (fried chicken), boiled sweet potato, and tomato salad. To eat the same thing, I need$ r 1,030 pesos. But I don’t add sugar or seasoning, and I haven’t included beans because poor people don’t cook beans, they eat rice with whatever they can. If I added seasoning, oil, and a little sugar, it would be 1,300 pesos a day,” said one of the families in Havana.

The rising cost of basic products is evident. The price of rice, an essential food, reaches 375 CUP per pound in some provinces, while beans reach 400–500 CUP. Pork, the main source of animal protein, exceeds 1,000 CUP per pound, and a carton of eggs costs between 2,500 and 3,900 CUP. Even previously accessible products such as sweet potatoes, cassava, and plantains have reached unthinkable prices, with bananas in Havana exceeding 100 CUP per unit.

The so-called “supply” booklet: a collapsed rationing system

The basket of regulated prices, once the pillar of the Cuban rationing system, is now virtually non-existent. Since May 2024, eggs have not been delivered through the ration book, and products such as oil, coffee, and chicken have almost completely disappeared from the rationed system. By mid-2025, monthly deliveries were arriving one or two months late, if they arrived at all, and the quantities distributed were minimal: in June, only 2 pounds of brown sugar, 1 pound of peas, and 1 packet of salt were delivered per person.

Cubans have lost confidence in the ration card and are increasingly dependent on the informal market or relatives outside Cuba who buy through foreign currency platforms such as Katapulk or SuperMarket23, online stores that sell basic products at dollarized prices. This duality has deepened inequalities: those who receive remittances can buy in these markets, while the rest are relegated to endless queues, prohibitive prices and, literally, hunger.

Inflation and its impact on food

Cumulative inflation since 2021 exceeds 220%, and in 2024 alone, the basic basket rose by 22%. The monetary reform of the so-called Tarea Ordenamiento in 2021 exacerbated the crisis by eliminating subsidies without creating conditions for a productive market. Today, more than 70% of family income is spent on food, although this figure is misleading: even if a worker spends their entire salary, they cannot cover their nutritional needs.

Lack of access to protein is one of the most serious consequences. While in previous decades chicken and fish were affordable sources of protein, today both are unattainable for the majority. The collapse of pork production and low fish catches have forced the country to rely almost exclusively on imports, which the government channels toward tourism rather than the population.

OCAC: a comprehensive proposal to ensure food security

The Cuban Observatory for Citizen Auditing (OCAC) proposes a comprehensive, far-reaching structural change to reverse the food crisis. In its analysis, the root of the problem is not only economic but also political. The GAESA monopoly and the state-run forced collection system of private production have strangled private non -state producers, which account for 80% of domestic food production despite receiving no incentives and having no freedom to operate.

OCAC reiterates its support to the five demands presented in 2020 by the association of independent farmers and the Cuban chapter of the Latin American Federation of Rural Women (FLAMUR) in their proposal “Without the countryside, there is no country,” which were ignored by the regime:

- Abolition of the monopoly on grain collection: Allow farmers to market their products freely, eliminating the obligation to sell a percentage to the state at ridiculous prices.

- Free market: Allow farmers to establish prices based on supply and demand to encourage production.

- Direct international trade: Authorize exports and imports without state intermediaries, including agreements with the US as allowed by Washington when trading with independent private farmers.

- Tax moratorium: Exempt producers from paying taxes for a decade to reinvest in infrastructure, technology, and machinery.

- Guaranteed private property: Grant permanent property titles over land and equipment to facilitate access to credit, insurance, and partnerships with investors.

OCAC’s expanded proposal: “Without the countryside, there is no country, and with GAESA, there is no future.”

However, given the worsening crisis, OCAC proposes going beyond these initial measures with an integral change that includes structural and legal reforms to allow for the development of a free and sustainable agri-food economy in the context of political and civil liberties, democracy, the rule of law, and a free market. Its recommendations include:

- Restructure economic power: Intervene and/or nationalize, audit, and dissolve GAESA and all its subordinated companies.

- Create an Agricultural Development Bank to finance producers with soft loans.

- Reform the legal framework, guaranteeing respect for private property and access to international arbitration.

- Open all the economy to the Cuban diaspora, allowing it to invest in agro-industrial projects.

- Promote the industrialization of the countryside through investment in irrigation, transportation, and food processing systems.

OCAC emphasizes that hunger in Cuba is not the result of external factors, but rather of a totalitarian political model that prioritizes the construction of empty hotels over agricultural production. The 2024 budget allocated 13 times more resources to tourism than to agriculture, a policy that has led to the current food collapse.

Conclusion

Food insecurity in Cuba is part of a systemic crisis that has left the population trapped between exorbitant prices and negligible wages. The basic basket of goods, which should provide the minimum necessary for survival, has become an unaffordable luxury. At least 30,000 CUP per month are required to eat poorly, an unattainable figure for most Cubans.

Hunger in Cuba is not an economic or climate problem, but essentially a political one. OCAC’s diagnosis is clear: without a comprehensive political and economic transformation, there will be no food on Cubans’ tables. Otherwise, hunger will continue to be the norm, not the exception.